Acute Renal Failure (ARF)

Acute renal failure (ARF) is a clinical syndrome associated with a rapid decline in renal function that occurs over a period of hours or days. It is characterised by complications resulting from the kidneys inability to regulate fluid, electrolyte, and acid-base balance and excrete metabolic waste products.

Acute renal failure (ARF) is also known as acute kidney injury (AKI). It is different from chronic kidney disease (CKD) or Chronic renal Failure (CRF) in terms of chronicity and other parameters.

Differences between ARF/AKD and CRF/CKD

| Parameter | Acute Renal Failure | Chronic Renal Failure |

|---|---|---|

| PCV | Increase | Decrease |

| Size of Kidneys | Large | Small |

| Onset of Disease | Suddenly | Insidiously |

| Reversibility | Reversible | Irreversible |

| BUN & Creatinine | Increase | Increase |

| Phosphorus | Increase | Increase |

| Pottasium | Increase | Decrease |

| Urine Output | Anuria or Oliguria | Polyuria |

Although ARF is not as common as CRF in dogs and cats, it causes significant morbidity and mortality in veterinary patients.

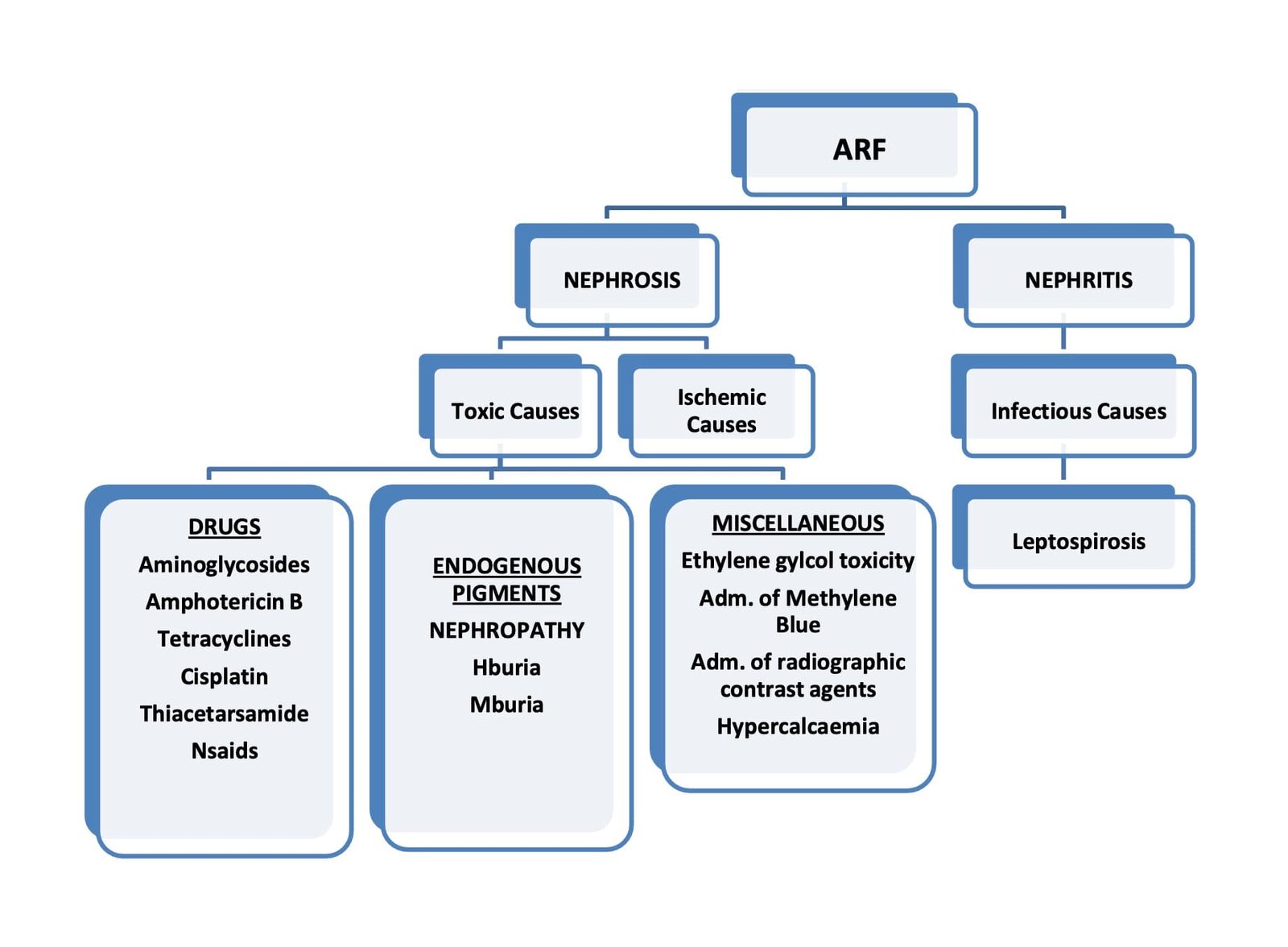

There are many potential causes of ARF, but only a few occur with any frequency. Most small animals develop ARF as a result of nephrotoxicosis; however, disorders such as leptospirosis and renal ischemia from the use of NSAIDs are being recognised with increased frequency.

Etiology

Ischemic Causes of Acute Renal Failure

- Hypovolumia: dehydration, Hg, hypoalbuminemia, hypoadrenocorticism

- Decreased cardiac output: CHF, pericardial disease cardiac arrhythmias

- Renal vasoconstriction: myoglobinuria, hemoglobinuria, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, captopril, enalpril

- NSAIDs: phenyl butazone, ibuprofen, naproxen, flunixin meglumine

- Renal vascular thrombosis: bacterial endocarditis, DIC, nephrotic syndrome, amyloidosis, glomerulonephritis

- Systemic vasodilation: anaphylaxis, inhalation anaesthesia administration, septic shock, heat stroke drugs (arteriolar dilators)

Diagnosis

Patients with ARF generally present with an acute onset of non-specific clinical signs that may include lethargy, inappetence, vomiting, diarrhoea, dehydration, and, in some cases, oral ulcerations. One should suspect ARF on the basis of these historical and physical examination findings.

Additional diagnostic techniques include lab examinations (for CBC, serum chemistry profile, and urine analysis), radiography, ultrasonography, serology, and, in selected cases, renal biopsy.

The results of the diagnostic findings should be used:

- To determine the presence of life-threatening complications.

- Distinguish pre renal, renal and post renal azotemia.

- Determine urine volume (oliguria from non-oliguria).

- Differentiate between ARF and CRF.

- Determine the specific causes of ARF.

Life Threatening Complications of ARF

Before performing an extensive diagnostic evaluation, one should first evaluate the patient for the presence of life-threatening abnormalities. This includes:

- Severe dehydration

- Hyperkalemia

- Severe metabolic acidosis

In some instances, treatment of their problems may be necessary before the results of initial laboratory tests are available. If at all possible, collect samples of blood and urine before administration and treatment. This will greatly facilitate the interpretation of results later, especially urine analysis.

- Early detection and correction of dehydration help prevent additional renal injuries due to hypoperfusion.

- Suspect hyperkalemia in patients with bradycardia or other cardiac arrhythmias. ECG changes associated with hyperkalemia may include prolonged PR intervals, spiked T waves, the absence of p waves, and prolonged QRS complexes. Immediate treatment is indicated in patients with >8 mEq/L to lower serum potassium concentration.

- Severe metabolic acidosis (pH <7.2 or total CO2 mEq/L) may also have detrimental effects on the cardiovascular system and should be treated to increase blood pH to above 7.2.

Localize Azotemia

This can be done on the basis of physical examination findings and urine analysis results. Dehydrated azotaemic patients with evidence of urinary concentrations (i.e., urine-specific gravity >1.030 in dogs and >1.040 in cats) most likely have pre-renal azotaemia.

Hypoadrenocorticism, hypercalcaemia, diabetic ketoacidosis, and diuretic or corticosteroid administration may be associated with pre-renal azotaemia and decreased urine sp. gravity.

The response to treatment may help distinguish between pre-renal and renal azotaemia. Azotaemia that resolves rapidly after pre-renal factors have been eliminated (e.g., dehydration) is most likely pre-renal in origin, whereas azotaemia that does not respond to the correction of a pre-renal condition is probably due to renal failure.

Post-renal azotaemia can usually be identified on the basis of the history, physical examination, and radiographic or ultrasonographic findings. Patients with lower urinary tract obstruction have signs of dysuria, stranguria, and pollakiuria. One should suspect post-renal azotaemia due to lower urinary tract obstruction in patients with anuria because pre-renal and acute tubular necrosis generally cause oliguria and anuria.

Determine Urine Volume

Although ARF often causes oliguria, it may be associated with non-oliguria (≥ 1.0 ml/kg/hr) in some cases. Amino glycoside nephrotoxicosis is probably the most common cause of non-oliguria ARF in small animal patients. The presence of non-oliguric kidneys indicated less severe renal damage and a more favourable prognosis than in the presence of oliguria.

Treatment of Acute Renal Failure (ARF)

The treatment or management of acute renal failure (ARF) is mentioned below:

- Identify treatable disorders and discontinue the administration of any potentially nephrotoxic agents.

- Correct fluid deficits and metabolic abnormalities.

- Characterise urine production (oliguria or non-oliguria).

- Provide fluid and metabolic needs for the maintenance phase of therapy.

- Reduce nausea and vomiting (ondensetron)

- Provide nutritional support.

- Monitor the response to the therapy.

- Treat the hyperkalemia if it exists.

- Reverse the oliguria if it exists.

Treatment of Hyperkalemia

| Type | Approx. Serum K+ conc. | ECG Changes | Therapeutic Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mild Hyperkalemia | 5.5 to 6.5 mEq/L | None | Volume replacement with K+ free fluids and initiation of dieresis should be sufficient. |

| Moderate Hyperkalemia | 6.6 to 7.5 mEq/L | Bradycardia, prolonged T waves, prolonged PR intervals, widened QRS complex | Sodium bicarbonate (0.5 to 2.0 mEq/kg IV) OR Dextrose (5–10% infusion) OR Regular insulin (0.25 to 0.65 U/kg IV) and glucose (1.2 g slowly IV per unit insulin administration) |

| Severe Hyperkalemia | >7.5 mEq/L | Absent P waves, idioventricular rhythm, ventricular tachycardia | Calcium gluconate 10% (0.5–1 ml/kg IV) and initiate therapeutic measures described for mild and moderate hyperkalemia. |

Treatment Strategies for Reversing Oliguria

- Ensure that volume deficits resulting from dehydration are corrected.

- Consider mild volume expansion by administering 3% body weight in replacement fluids.

- Administration loop diuretic frusemide at 2-3 mg/kg body weight IV.

- If successful, repeat every 6–8 hours as needed. If unsuccessful, administer 4-6 mg/kg IV at one-hour intervals at 2 and 3 hours following the initial dosage. If frusemide alone is unsuccessful after several hours, administer vasodilators or osmotic diuretics with frusemide, like dopamine, at 1–5 mg/kg/hr.